Special Purpose Acquisition Companies, or SPACs, seem to be all the rage recently. But why are they gaining so much attention, and what should investors know?

IPO. EPS. MLP. LIBOR. NYSE. The investment world is fond of acronyms and keeping them straight can be a tall order for investors. SPAC, the latest one gaining popularity, stands for Special Purpose Acquisition Company, and it doesn’t appear the wave of attention for these so-called “blank-check” companies will be slowing down anytime soon. In this article, we’ll answer several common questions about SPACs and discuss where they fit in the broader investment opportunity set.

What purpose do SPACs serve?

A SPAC is an investment vehicle whose main function is providing the means to take a private company public. Private companies have several choices if they want to go public and, historically, many have undergone their own initial public offerings, or IPOs.

With a SPAC, the sponsor raises assets through its own IPO with the intent of using the proceeds to purchase a yet-to-be-identified private company that is later “acquired” and effectively taken public. The sponsor has a defined period in which to find and acquire the potential target company–typically two years, but it varies–otherwise, cash from the IPO is returned to investors.

After the SPAC sponsor identifies and signs an acquisition agreement with a target company, the shareholder approval process and various SEC filings follow. Interestingly, when the business combination is proposed, shareholders have the option of redeeming their shares for cash. Alternatively, if they maintain their investments, which typically comprise both common shares and warrants (or the right to purchase additional shares in the future), they become shareholders of the operating company upon completion of the merger.

Are SPACs new?

SPACs are not new, but the capital raised in traditional IPOs has historically been much more significant than that raised in SPACs. For example, from 2013 to 2019, traditional IPOs raised almost $268 billion versus just $43 billion in SPACs.1 But in 2020, SPAC issuance exploded to almost 250 listings totaling more than $83 billion. This trend has continued in 2021, with an additional 165 SPAC IPOs totaling almost $50 billion to date.2

The recent rise in SPAC activity is worth evaluating within the context of the broader market environment. Global equity issuance in 2020 exceeded $1 trillion for the first time in history, with secondary offerings accounting for more than double the amount of capital raised in IPOs.3 This points to broader demand from companies seeking access to public capital markets amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Why would a private company choose to go public via a SPAC versus a traditional IPO?

A multitude of tradeoffs could influence this decision. The most frequently cited potential benefits of SPACs include time (SPAC mergers can happen faster than traditional IPOs), price certainty (the sponsor and target company negotiate the acquisition price), and the ability to market to a broader audience of investors with fewer restrictions on the marketing materials shared with them.

In a traditional IPO, a company holds a roadshow two weeks before the listing and has strict limitations about the information it may share with potential investors. These limitations are not as restrictive in a SPAC merger, as the SPACs and merger targets benefit from a safe harbor against liability for using projections and forward-looking statements.

Are SPACs good investments?

The short answer: It depends. While you may have seen headlines about large business combinations and some outsized returns, the comprehensive data paints a different picture. If the goal is to “get in on the ground floor” of a new public company, then investors should consider the returns of the SPAC after completion of the merger. A recent study from academics at Stanford and NYU analyzed all 47 SPACs that merged between January 2019 and June 2020.

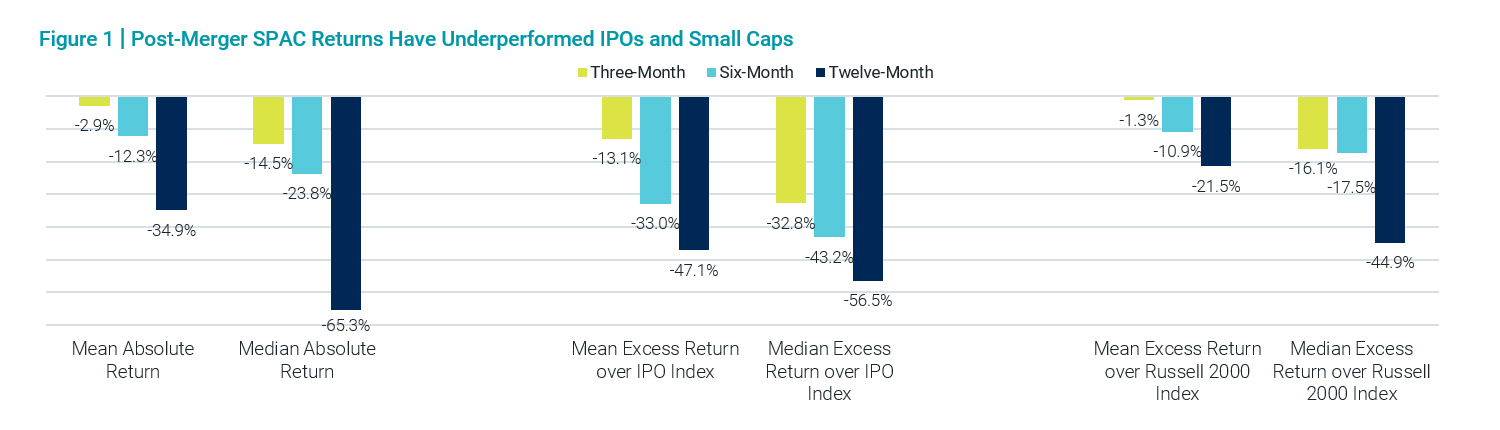

The authors found that while the returns across SPACs varied widely, the median and mean absolute returns and relative returns versus an IPO Index and the Russell 2000® Index (a small-cap benchmark) were all negative in the three-, six- and 12-month periods following the SPAC merger.

Source: Michael D. Klausner, Michael Ohlrogge and Emily Ruan, A Sober Look at SPACs (October 28, 2020). Stanford Law and Economics Olin Working Paper No. 559, NYU Law and Economics Research Paper No. 20-48, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3720919 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3720919. Data reflects the 2019-2020 merger cohort. Of the 47 SPACs examined, 47 had sufficient history for the three-month period, 38 for the six-month period and 16 for the 12-month period. The IPO Index is the Renaissance IPO Index.

The Renaissance IPO Index® (IPOUSA) is a stock market index based upon a portfolio of U.S.-listed newly public companies that includes securities prior to their inclusion in core U.S. equity portfolios.

To see if this finding was merely a chance result, they extended their analysis back in time, looking at the average one-year post-merger returns relative to the Russell 2000 Index for earlier SPACs. To quote the authors,

“As the results show, there has never been a year in which SPAC mergers outperformed the Russell 2000. Even the best of years underperforms by 10% within the first-year post-merger, and many years see excess returns of negative 40% or more.”

It is important to note the returns experienced by SPAC sponsors, which receive shares in the business combination for a nominal amount of capital (referred to as the “promote”), have been much higher. The aforementioned study found the average 12-month return for sponsors of the SPACs examined was 187% (the median return was 32%). This appears to suggest SPACs are better deals for sponsors than investors.

A third group of investors invest initially in the SPAC IPO but redeem their shares before completion of the merger. Evaluating their returns is more difficult, as many would have received cash plus some level of interest and, depending on terms of the agreement, may have been able to retain warrants to purchase shares of the operating company in the future. But data from 13F filings shows most SPAC IPO investors are large institutions, such as hedge funds.

So, what’s the bottom line? Should I consider adding SPACs to my portfolio?

Some SPACs have come to market with non-traditional terms, attempting to create more alignment between sponsors and investors. Only time will tell if investors in these SPACs might fare better.

In the interim, we believe commonsense investment principles should apply. The terms of each deal, your rights as an investor, the sponsor’s incentives, etc., all matter in determining if a SPAC may be a viable investment. Even if all those boxes can be checked, it ultimately remains an investment in a single company, so the outcome is based almost entirely on the ability of that company to succeed.

Diversification is one of the most basic principles of investing, and its benefits are always worth remembering. Success in investing is not dependent on picking the best single company. Over the long-term, market returns have historically demonstrated that diversified investors have been rewarded.

Prepared in collaboration with the Perigon Investment Team & Avantis Investors – March 2021

1Goldman Sachs Investment Research.

2SPACInsider. Data as of 2/23/2021. https://spacinsider.com/stats/.

3“Global IPO Watch – Q4 2020,” PWC Global. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/audit-assurance/ipo-centre/global-ipo-watch.html.

An investment in SPACs presents different risks depending on what point in the SPAC life cycle shares are purchased including the risk that the acquisition may not occur or that the customer’s investment may decline in value even if the acquisition is completed. Investors who purchase in the secondary market after an acquisition announcement may suffer a loss if the value of the shares subsequently declines. There is also the risk that SPAC managers are inexperienced or unqualified and this risk can be made more pronounced by lack of any operating history or past performance of the SPAC.